For over more than 10 years, since the creation of Astrobin by Salvatore Iovene, asteroid observations have been reported by Astrobin members. As I am interested in asteroids myself, I have assembled a list of these observations, and am keeping it up to date when new observations are reported.

As of today, this list features almost 900 individual observations of over 660 unique asteroids reported by more than 260 Astrobin members. The size of the observed asteroids range from the largest (Pluto, Ø=2376.6 Km) to asteroids as small as 164207 (2004 GU9) with a diameter of 0.163 Km. The observed asteroids belong to 26 groups, ranging from main-belt asteroids to transneptunian objects. Among the observations we find Apollo, Amor, Aten, Centaur and Jupiter Trojan asteroids, as well as a Sednoid.

The full list can be accessed here.

Sometimes, asteroids are the target of these observations, especially when they are of particular interest, such as Near Earth Objects (NEO). One example is 7482 (1994 PC1) reported in January 2022 by Yizhou Zhang, showing the movement of the asteroid against the background stars.

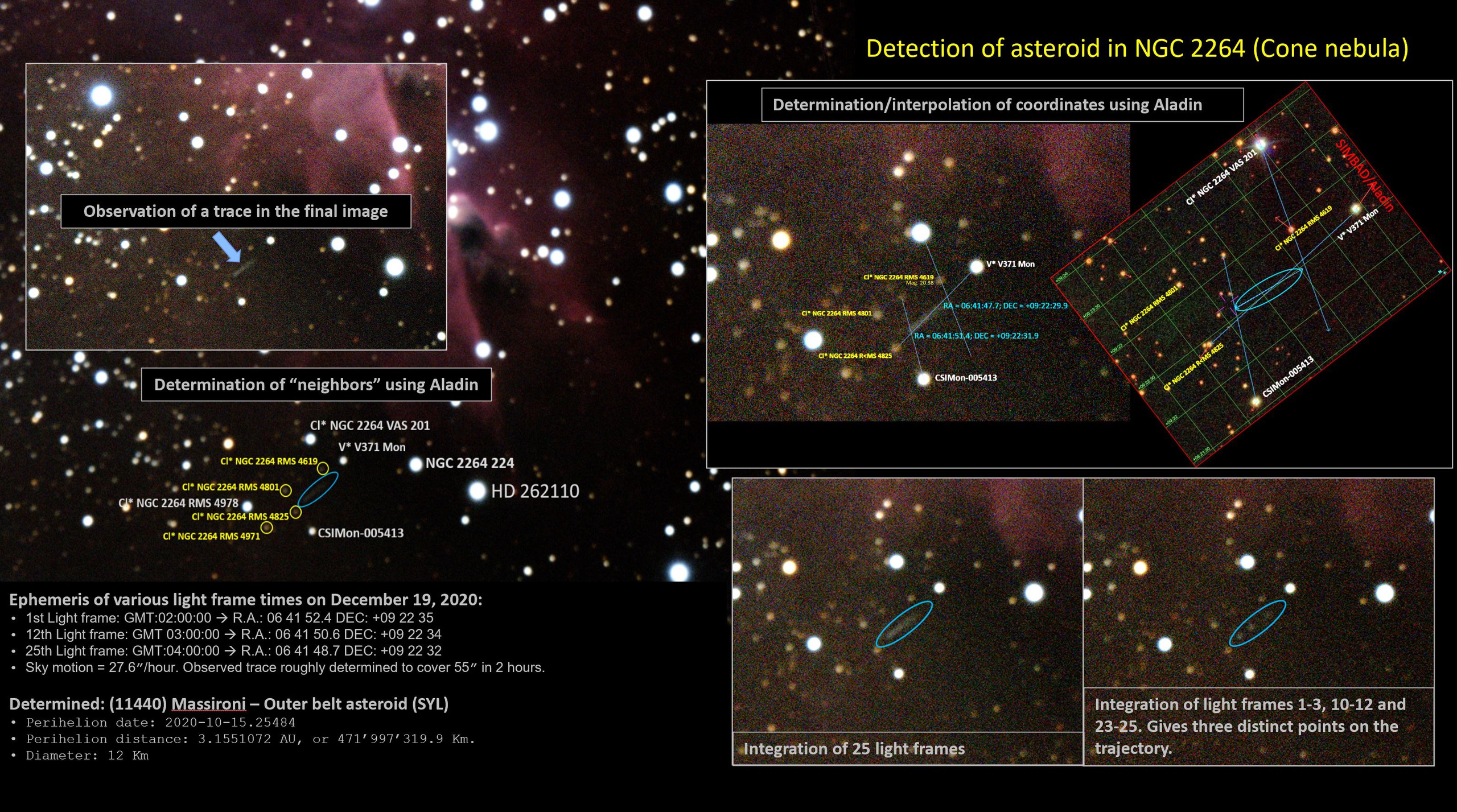

However, most asteroid observations on Astrobin are fortuitous. They are “caught” while imaging a deep sky object and later detected and identified. Many astrophotographers are attracted by a trace left by the asteroid following the stacking process. I “caught” my first asteroid in December 2020, while I was collecting images of NGC 2264 (the Cone nebula in Monoceros). At the time I used a cumbersome combination of Aladin and ephemerids generated by MPCheck to identify asteroid 11440 Massironi (1975 SC2).

Identification of my first asteroid caught while imaging a deep sky object:

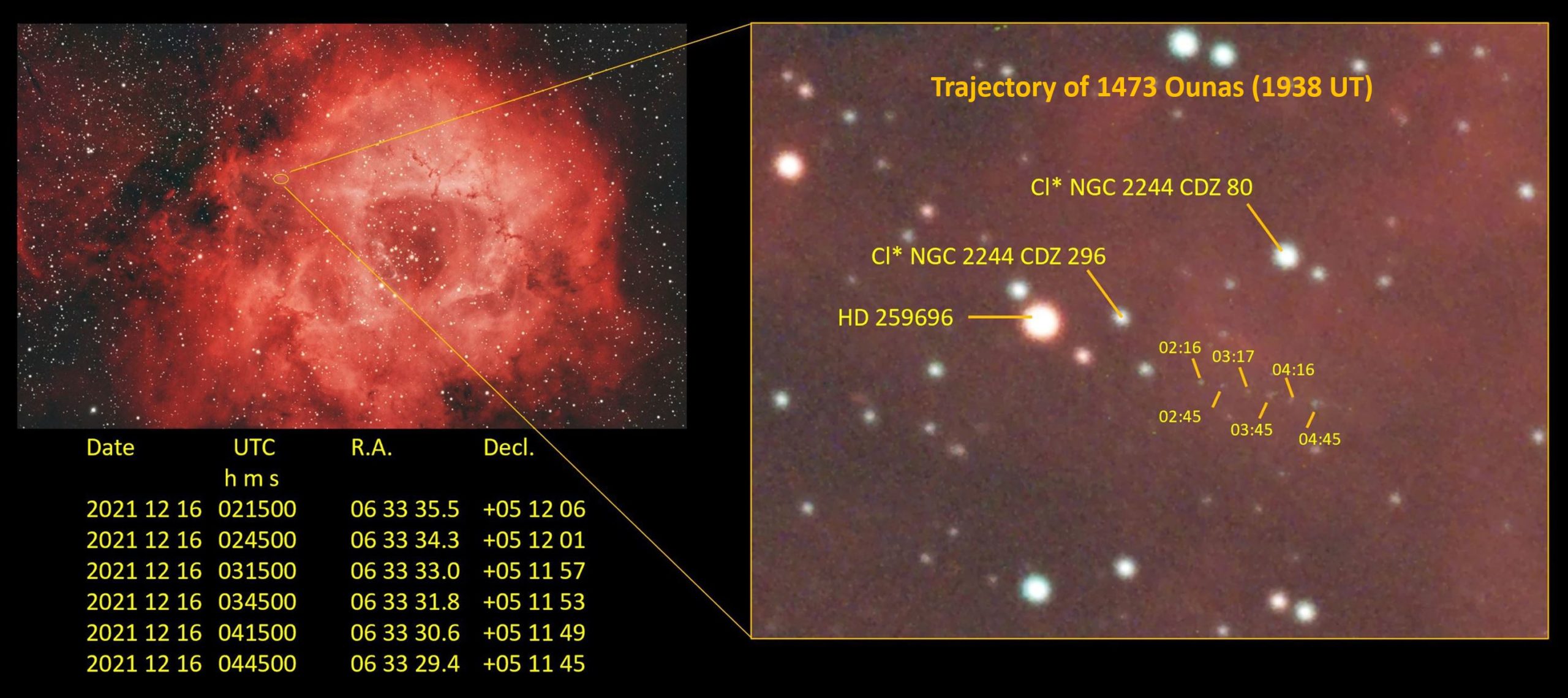

Only later did I start using ASTAP to identify asteroids in the light frames directly, followed by visual inspection of the integrated image and verification of its identity using MPCheck. This allows to detect asteroids that are less obvious to see on the integrated image. For example, in the image below, I identified the main-belt asteroid 1473 Ounas (1938 UT), which is “hidden” in the Rosetta nebula where it left only a very faint trace in the stacked images. I could only make it out because I knew it should be there. However, by stacking 3 light frames every 30 min, the presence of the asteroid became obvious as shown by the succession of light points on a straight line. The coordinates of these points correspond to the ephemeris of Ounas over the time frame the image was taken.

It happens that a transneptunian object (TNO) first identified as an asteroid (with an unusual orbit) is later reclassified as a comet, when it displays features of a comet, like a little fuzz. For example, A/2013 UQ4 was reclassified as C//2013 UQ4 (Catalina) when it grew a little fuzz, discovered by amateur astronomer Taras Prystavski, who also has an asteroid named after him: 335533 Tarasprystavski (2006 AH83). Similarly, the TNO A/2019 K6 which was reclassified as C/2019 K6 (PANSTARRS).

In summary, I have learned a lot about asteroids over the last couple of years, and it is always rewarding to spot and identify them. Clearly, with well over a million known asteroids, discovering a new one is not within reach of the equipment most astrophotographers use (due to magnitude limitations), but that does not diminish my interest in this activity.